When I first read the news announcement related to a major new discovery of a 7th or 8th Century document called the Ashkar-Gilson Manuscript, it reminded me of a quote I first heard over 25 years ago.

Archaeology has not yet said its last word; but the results already achieved confirm what faith would suggest, that the Bible can do nothing but gain from an increase of knowledge.

Sir Frederick Kenyon

I was excited to hear more detail related to this new discovery. As Sir Frederick Kenyon said, the Bible would gain from this find once it had been studied to the fullest extent. Finding an ancient document from the 7th or 8th Century AD could only fill in the gaps in the story of textual transmission and add more valuable information. For the outline of the previous state of play I would suggest you read the Nuggets I wrote on The Oldest Portion of the Bible in Existence concerning Gabriel Barkay’s discovery of the oldest existing portion of the Bible in 1985 and follow it up with The Remarkable Find at Qumran related to the discovery of the Qumran Isaiah B scroll (1QIsaB) in 1947 by three Palestinian Arab boys. In fact if you really want to know more of the details, I suggest you follow all the Nuggets in the series Textual Transmission. However for this latest discovery allow me to give you a brief run down on the significance of this latest find.

The Ashkar-Gilson Manuscript

The Ashkar-Gilson Manuscript is truly a missing link in the story. This manuscript fills in the gap between the full text that we have currently in the form of the Aleppo Codex and Leningradensis both dated around the 10th to 11th Centuries AD and the text available to us from the Dead Sea Scrolls dating from 250 BC and 68 AD. The importance of this find is that it can fill in the middle ground between the text evident from the Dead Sea Scrolls and that which is available in the earliest full texts of the Bible we have in the Aleppo and Leningrad Codices. I have already told you of the astounding fact that the texts vary so little between that which was found in Qumran and that which we know to be the text of the Bible 1000 years after Christ. I have explained how that is possible in the series of Nuggets I have written on the Textual Transmission process. Now we have another new text for the text experts to work with. Actually in reality we have more than that available. I have told you already the story of the findings among the Qumran Scrolls. What I have not told you is that the Qumran Scrolls now number over 80,000 scrolls and fragments found across 11 caves. There is still a massive amount of work to be done on those scrolls in order to reveal the content of them all.

In the days when I was sharing the detail I had gathered in the God’s Awesome Book Seminar, I would tell people of the 13,000 documents of the Bible available for research into the text of the Bible. Daniel Wallace and the team working at the The Center for the Study of New Testament Manuscripts (CSNTM) have now gathered and are working on digitalising all of the available manuscripts. That may sound impressive, but allow me to give you an inkling into just how impressive it really is. I hesitate these days to tell audiences just how many manuscripts related to the Bible there are in existence. In 2019 the CSNTM were working in collaboration with more than 45 institutions on 4 continents to produce nearly 300,000 images from approximately 700 New Testament manuscripts. In the process, they have discovered over 75 New Testament manuscripts that were previously unknown. Their online library features images or links to more than 1,700 manuscripts and has been made available to over 50,000 New Testament scholars to to use in their research. The most up to date total from Josh McDowell’s Evidence that Demands a Verdict puts the total figure over 27,000 documents of attestation. I don’t quote the total figure anymore because it is growing too rapidly.

The first list of the Old Testament manuscripts in Hebrew was made by Benjamin Kennickott (1718–1783) and published by Oxford in 2 volumes in 1776 and 1780, listing 615 manuscripts from libraries in England and on the Continent. The main manuscript discoveries in modern times are those of the Cairo Geniza (c. 1890) and the Dead Sea Scrolls (1947). In the old synagogue in Cairo were discovered 260,000 Hebrew manuscripts, 10,000 of which are biblical manuscripts. I can honestly say we have an abundance of Biblical documentary evidence gathering momentum as the teams of researchers begin to work together, especially on the Dead Sea Scrolls and the more recent finds I have commented on. You can go online to see listings of the documents found in the caves at Qumran, but you will have to wait with everyone else to learn the details contained within each manuscript. As I have said before in this series, examining ancient scrolls is painstaking work. The exciting thing about the Ashkar-Gilson Manuscript is that it is not part of the DSS collection and is being worked on by a different team.

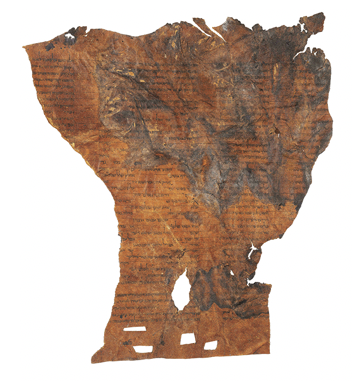

The Ashkar-Gilson Manuscript is so-called because it was purchased by Fuad Ashkar and Albert Gilson from an antiquities dealer in Beirut, Lebanon in 1972. Some years later they donated it to Duke University in North Carolina. Based on carbon-14 dating and paleographic analysis, the Ashkar-Gilson Manuscript was dated to sometime between the seventh and eighth centuries AD. However in those initial years it took some time for those who had it in their possession to realise what a treasure they had. In the early years after discovery it was overlooked by scholars, considered to be unimportant to the research into the text families and so it remained unpublished. Furthermore, the manuscript was severely damaged and blackened, making it difficult to read in parts. It contains only excerpts from the consonantal text of Exodus 13:19 –16:1.

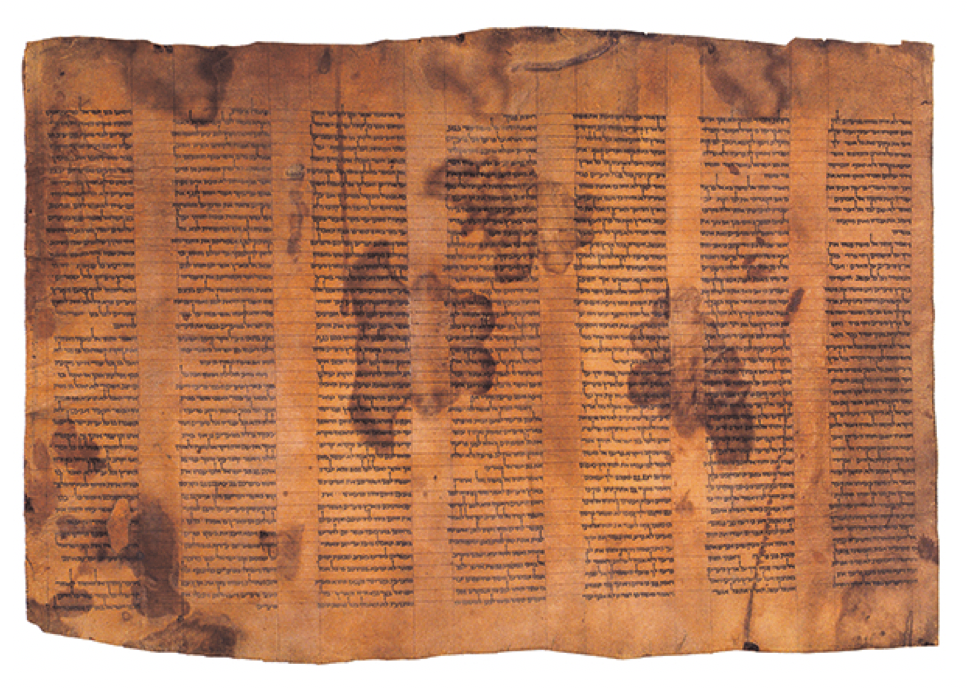

Since 2007, the Ashkar-Gilson Manuscript has been on loan in the Shrine of the Book of the Israel Museum in Jerusalem. However, it will soon return to Duke University, where it will be housed in the David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library. While the sheet was on display in the Shrine of the Book, two Israeli experts, Mordechai Mishor and Edna Engel, noticed that the handwriting and layout reminded them of a better-preserved sheet of a Torah scroll, known as the London Manuscript, which contains the text of an earlier passage: Exodus 9:18–13:2. The two scholars had seen a photo of the London Manuscript in the Encyclopaedia Biblica (1968). The London Manuscript too had been disregarded by the scholarship.

The London Manuscript

Following some additional research, it was established that the London Manuscript was a remnant of the same Torah scroll type as the Ashkar-Gilson Manuscript. Both the Ashkar-Gilson Manuscript and the London Manuscript contain the same consonantal text of the Masoretic codices of several centuries later. Since 1947 the text of Exodus has been missing from the Aleppo Codex, the most accurate of the early codices, but its text can be reconstructed with certainty. The text of the Masoretes agrees completely with the text of the Ashkar-Gilson and London Manuscripts. Now all eyes are on the comparison between the Ashkar-Gilson Manuscript and the London Manuscript.

We will look in more detail at the nature of this discovery in the next Nugget.

an interesting read.