I told you in the previous Nugget, how two Israeli experts, Mordechai Mishor and Edna Engel, noticed the similarities in handwriting and layout of the text of Exodus 9:18–13:2 while the sheet was on display in the Shrine of the Book in Jerusalem. It reminded them of a better-preserved sheet of a Torah scroll, known as the London Manuscript, which contains the same text. The two scholars had seen a photo of the London Manuscript in the Encyclopaedia Biblica (1968).

In May 2014, Paul Sander obtained an infrared photo of the Ashkar-Gilson Manuscript from the Israel Museum and spent a year making a detailed comparison of the text and layout of the Song of the Sea. The results of his study were published in the article Missing Link in Hebrew Bible Formation at the end of the following year in the Biblical Archaeology Review.1

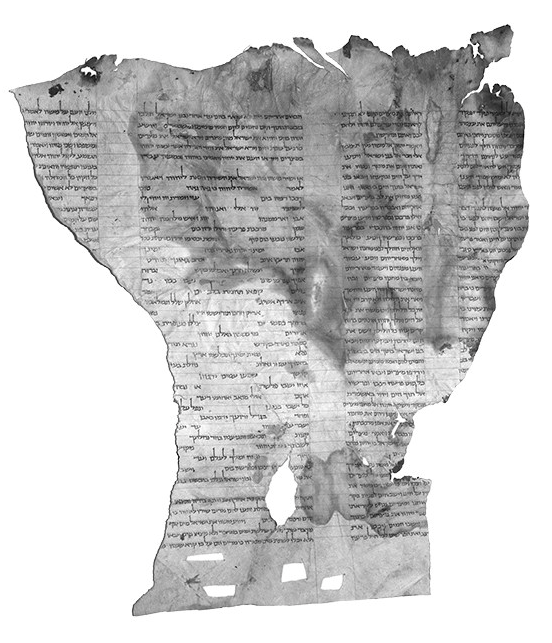

The Infrared Photo of the Song of the Sea

What is remarkable is the clarity of the infrared photo compared with the photo of the Ashkar-Gilson Manuscript I showed you in the previous Nugget. Infrared photography is a major tool in studying ancient manuscripts which are damaged or hard to read. This is evidenced in the case of Palimpsests as I wrote about in a previous Nugget in the Textual Transmission series – The Two For One Deal. Infrared photography can capture the clarity of the text even when one text is superimposed on another at right angles as seen in the palimpsests2.

Given this clarity of text in an infrared digital image, Paul Sander was able to compare the text of the Song of the Sea in the Ashkar-GIlson Manuscript with the same text in the London Manuscript. The text found in the two codices matches completely. Here is yet another example of the scribal accuracy of the Masoretes and their intricate procedures for copying the text, as found in the comparison of the Dead Sea Scroll of Isaiah B and Codex Leningradensis. The copying of the consonantal text was meticulously carried out to ensure a faithful copy was produced. While we only have a small section of the text preserved in the case of the Song of the Sea, it is safe to assume, given all the other evidence we have, that this same careful attention to copying the text was applied across the entire codex. This proves that Masoretic processes preserved the consonantal text well. At a later stage they added the vowels using a system of dots and dashes which we know as the vowel pointings of modern Hebrew.

However, Paul Sander found more exciting evidence in his comparison of this ancient Song of the Sea (Exodus 15). Moses and the Israelites sang this hymn after God had parted the sea for them and then drowned Pharaoh’s pursuing army. This song (psalm) is one of the oldest passages of the Hebrew Bible.

“I will sing to the LORD, for he has triumphed gloriously;

he has hurled both horse and rider into the sea.

The LORD is my strength and my song; he has given me victory.

This is my God, and I will praise him

my father’s God, and I will exalt him!”

Exodus 15:1-2

I remember this segment of the song because we used to sing it in church at the end of the 1970s. This is one of the oldest parts of the Bible, yet it has come down to us faithfully preserved over the intervening millennia. That is remarkable; the same song Miriam sang, we now sing in this day and age. You can sing the whole of the song for yourself by reading it as recorded in Exodus 15:1-18 and adding you own tune if you don’t know the tune sung in the 1970’s. The Masoretes copied this song with the utmost care.

But there is more to the story. It seems they were aware of the uniqueness of this song and the need to preserve its textual appearance too.

They copied it in a special symmetric layout that resembles brickwork, with two blank spaces in the even lines and one blank space in the odd lines. This arrangement was chosen not only for its beauty but also for its meaning, with each of the spaces marking the end of a colon (a small poetic unit that must be sung in one breath). The importance of this brickwork layout is reflected in the fact that it is reproduced in every Torah scroll used in synagogues today. (A similar layout is required only for the Song of Deborah in Judges 5, another old and exceptionally beautiful poem.)

Paul Sanders

In the Dead Sea Scrolls, the Song of the Sea does not have this same layout. Yet it appears in the Ashkar-Gilson Manuscript! This marks the first time the brickwork pattern is found, without any deviation from the later arrangement found in the London Manuscript. In the Ashkar-Gilson Manuscript, some minor details in the columns with the song are accidental. These details concern the layout, as well as the column’s coincidental start with an ordinary Hebrew word (הבאים) meaning “that went in” (namely, into the sea; Exodus 14:28).

Remarkably enough, even these insignificant details are also found in the oldest Masoretic codices. But there they are not accidental. The copyists had to make a special effort to reproduce them as faithfully as possible. For instance, they compressed or spaced out the text in the preceding columns to let the column with the Song of the Sea start with exactly the same word as the column in the Ashkar-Gilson Manuscript. Even the copyists of the more recent Torah scrolls did their best to reproduce these seemingly insignificant details.

How can this be explained? I think there is only one convincing solution: The very Torah scroll of which the Ashkar-Gilson Manuscript and London Manuscript are remnants was consulted by the Masoretes of Tiberias. In other words, this seventh- or eighth-century Torah scroll must have figured prominently when they produced the now-standard text of the Hebrew Bible.

Paul Sanders

The Masoretes were seemingly compelled to maintain the “brickwork” layout of the original because of its poetic beauty and layout. Other copying features of the ancient Torah scroll are also impressive and match the highest standards of the early Middle Ages when the layout of poetry was so ornate.

The sheets were dry-ruled before being inscribed—both vertically, to demarcate the margins of the columns, and horizontally for the individual lines. Also, the height of the columns conforms to the early medieval rule that a column of a Torah scroll must be 42 lines high. The text was written with a firm hand, and the copyist observed the ruled margins, trying to avoid protrusions beyond the margin line. Such features indicate that the Torah scroll was a first-class manuscript that deserved to be copied. So it is quite understandable that the Masoretic copyists selected this scroll.

Paul Sanders

All of the above is strong evidence to suggest that the very document and its idiosyncratic layout and formatting has been copied to perfection. This really is remarkable because we see in this process, it is not only the text itself which has been copied but the layout as well including some of the minor details along with line breaks. The Ashkar-Gilson Manuscript displays the appearance of text of the Song of the Sea and its content, thereby providing crucial evidence for the use of that particular scroll in the creation of the Masoretic text still used in synagogues today. We are not saying that this is the autograph, the original from which all others were taken. Many scrolls were hand scripted in the Scriptorium. But what is remarkable here is that we have this copied feature of not just the text plain text but the layout as well. What we do see from this example is that there was flexibility in the transmission of the text, whereby some idiosyncratic features have come down to us. We can conclude that the Masoretic text is the end result of a long process of faithful transmission along with a degree of flexibility in the way the text was presented. It is also clear the period between the second and sixth centuries A.D. must have been one of gradual stabilisation of the Biblical text. The surviving Dead Sea Scrolls that were written after the first Jewish revolt (post-70 A.D.) show a Biblical text that is already relatively close to the Masoretic text. The evidence we have for the faithful transmission of God’s Word is strong.

The following centuries beyond the seventh and eighth must have seen the work of the Masoretes further stabilise and normalise the text of the Jewish Old Testament. The Ashkar-Gilson and London Manuscripts prove that this process of stabilisation had already come to an end some centuries before the Masoretes started to produce the earliest Bible codices. It has been assumed that the Masoretes were the ones to begin the process of text standarisation. Now we can see they reproduced a text that had already been stabilised and no longer allowed any deviations. It was not their goal to innovate—but rather to preserve the finest textual traditions that existed at the time.

Footnotes

1. Missing Link in Hebrew Bible Formation by Paul Sander published in the Biblical Archaeology Review November-December 2015, Vol 41. No 6.

2. Palimpsests – Manuscripts found that have been washed scraped and re-used. One text written in portrait format while a second text has been written over the top in a darker landscape format.